💡Bottom Line Up Front

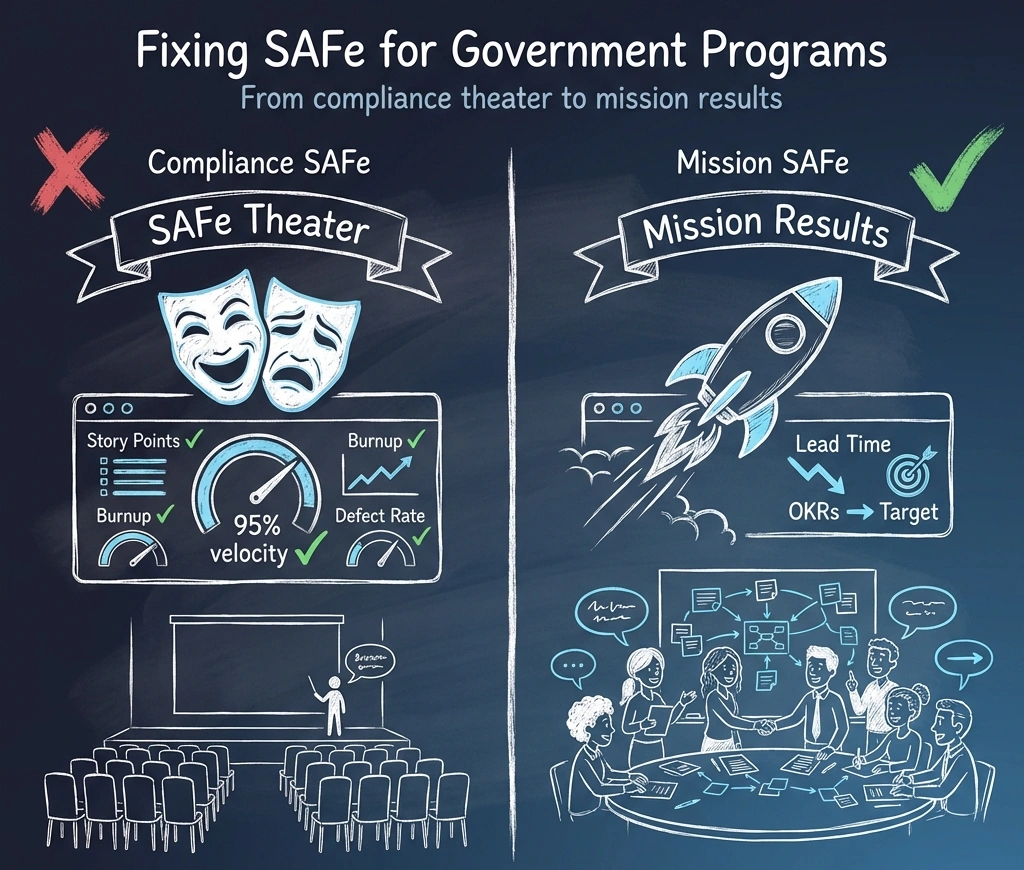

SAFe isn't failing your program. "Compliance SAFe" is. When 55% of organizations say they have visibility into the software development life cycle (SDLC) but 63% agree they struggle to deliver reliable, high-quality software, the problem isn't the framework. It's organizational silos that separate requirements from delivery, contracts that reward bad behavior, and agile events run without the users who actually own the mission. The fix: mission "readiness assessments" to set or repair joint expectations, unified governance, badgeless multi-vendor teams, and flow-based metrics tied to mission results.

In this article: We contrast Compliance SAFe vs. Mission SAFe, diagnose multi-vendor failure modes, and provide the Mission-Results Protocol to drastically improve delivery performance.

The Green Dashboard, Red Mission Problem

All the indicators look great: your PMO dashboard is green, PI Planning attendance is at 95%, velocity is trending upward, and ceremonies happen like clockwork.

But the modernization is a year behind. Costs have grown. The legacy system is still running. Users are still waiting.

Welcome to SAFe Theater. We know senior leaders don't intend this. It happens when perfecting the framework and complying with policy becomes more important than delivering value.

⚠️The Visibility Paradox

The 18th State of Agile Report (2025) exposes a striking contradiction: 55% of organizations now report "complete visibility across the software development life cycle (SDLC)," while 63% simultaneously "struggle to deliver reliable, high-quality software."[] That's a 12% increase in delivery struggles year-over-year. More visibility. Less reliability. How is that possible?

Government data tells the same story. A 2024 GAO assessment found that only 4 of 21 major DoD IT programs met all performance targets, and 4 of 10 programs using Agile lacked the required metrics to track customer satisfaction and development progress.[] While this study focused on DoD, the patterns apply equally to civilian agencies where divided governance and stakeholder capacity constraints are just as severe.

The pattern plays out because visibility into the wrong things doesn't fix broken systems. And in government, SAFe has too often become a calendar of events layered on top of slow decision-making, too few mission staff, roadmaps that never change, and governance structures that prevent real reprioritization.

This isn't an execution problem. It's a design problem.

Compliance SAFe vs. Mission SAFe

There are two ways to run SAFe in government. Only one of them ships software that matters.

Compliance SAFe (Checking the Boxes)

If you walk into a program running in this mode, the warning signs are clear in every meeting. You'll recognize it by these common symptoms:

A senior leader who spent seven years on a major VA SAFe implementation calls this "delivery theater." It looks like agile. It sounds like agile. But it cannot ship software that matters because nothing in the operating model has actually changed.

When key experts and stakeholders "have full-time jobs," when requirements are handed off from disconnected silos, and when leadership can't staff enough mission staff, the train runs on assumptions, rework, and late-stage surprises.

Mission SAFe (Delivering Actual Software)

In contrast, a mission-focused implementation feels different. The focus shifts from activity to outcomes. You'll recognize it by these behaviors:

The difference isn't just effective agile events. It's the delivery model underneath.

Where the Wheels Fall Off: Lessons from the Field

The same VA practitioner mentioned earlier identified what went wrong. These aren't theoretical. These problems have delayed federal programs and driven up costs.

"The Roadmap Was Static for a Couple of Years"

In one large modernization, the implementation roadmap stayed static for years even though everyone knew it was unachievable. The program wasn't allowed to change it without senior leadership approval, which wasn't given.

💡The Fix

Set expectations with leadership upfront: timelines will change. Avoid fixing dates until you have enough real progress (i.e., a history of software tested and deployed) to project where you'll be 3-5 years out. If your roadmap doesn't change, you aren't learning. And if leadership resists schedule changes because "we already committed," you've created a culture where programs hide reality instead of adapting to it.

"We Were Too Accommodating to Current Processes"

Programs often bend too much to old processes to avoid friction. Teams recreate old systems in new tech, adding costs and complexity.

💡The Fix

Define acceptable change limits upfront. Users should expect to adapt their processes to the new system rather than the other way around. If leadership won't make policy tradeoffs, SAFe won't help you.

But this isn't a license to require strict rules. The goal is solving real mission challenges, not enforcing consistency for its own sake. When a partner organization has a legitimate constraint (e.g., a process tied to patient safety, a regulation that can't be waived), work through it.

"Partner Organizations Follow Their Own Governance"

Governance often fails across partner administrations and program offices that follow independent timelines and priorities. SAFe events cannot outrun teams working at different speeds.

What happens: The fastest Agile Release Train (ART) is constrained to the slowest decision loop.

💡The Fix

Establish unified governance agreements and a single decision-rights map before execution. Determine which decisions are made at team/ART/exec level and create an escalation path that works at mission speed (days, not weeks or months).

"We're Going In Blindly"

Modernization programs often onboard partner organizations without knowing their readiness. The result: interfaces discovered mid-implementation that depend on external vendors working on different timelines, critical SMEs who can't be freed up, and undefined policies that stall decisions. All preventable with early planning.

💡The Fix

Implement a Partner Readiness Protocol. Six to twelve months before you expect to begin implementation with a partner organization, run a structured readiness assessment and workshop. Document the results in a formal agreement (MOU or Partner Working Agreement) that sets joint expectations before the train tries to leave the station.

The partner readiness assessment sets expectations for working together and documents the partner organization's readiness to begin implementation. It includes:

Common gaps you'll surface:

A typical scenario: A program office has 2-3 critical SMEs. The modernization effort needs 25-50% of their time during key implementation phases. The program office says they can't commit because those SMEs are the only people who know the legacy system.

With 6-12 months of lead time, you can address the situation. Roll on contractors to document what they know and provide partial coverage. This doesn't fully replace the SMEs, but it frees up enough of their time for the implementation to succeed. It also addresses the knowledge risk: the documentation captures what was previously in their heads.

But this only works with advance planning, potentially a separate contract action, and explicit leadership buy-in. Start the readiness conversation late, and you absorb the delay and quality risk into your schedule. Start it early, and you turn a blocker into a solution that helps address the knowledge gap now and in the future.

The Multi-Vendor Trap & Contracting for Success

Multi-vendor environments are the norm in federal IT. They are also a place where SAFe implementations often struggle. The reason is not because the framework can't handle multiple vendors, but because contracts accidentally prevent teamwork. They measure the wrong things and don't reward the right actions with incentives.

This structural challenge has a name: Conway's Law. It's been documented since the 1960s.

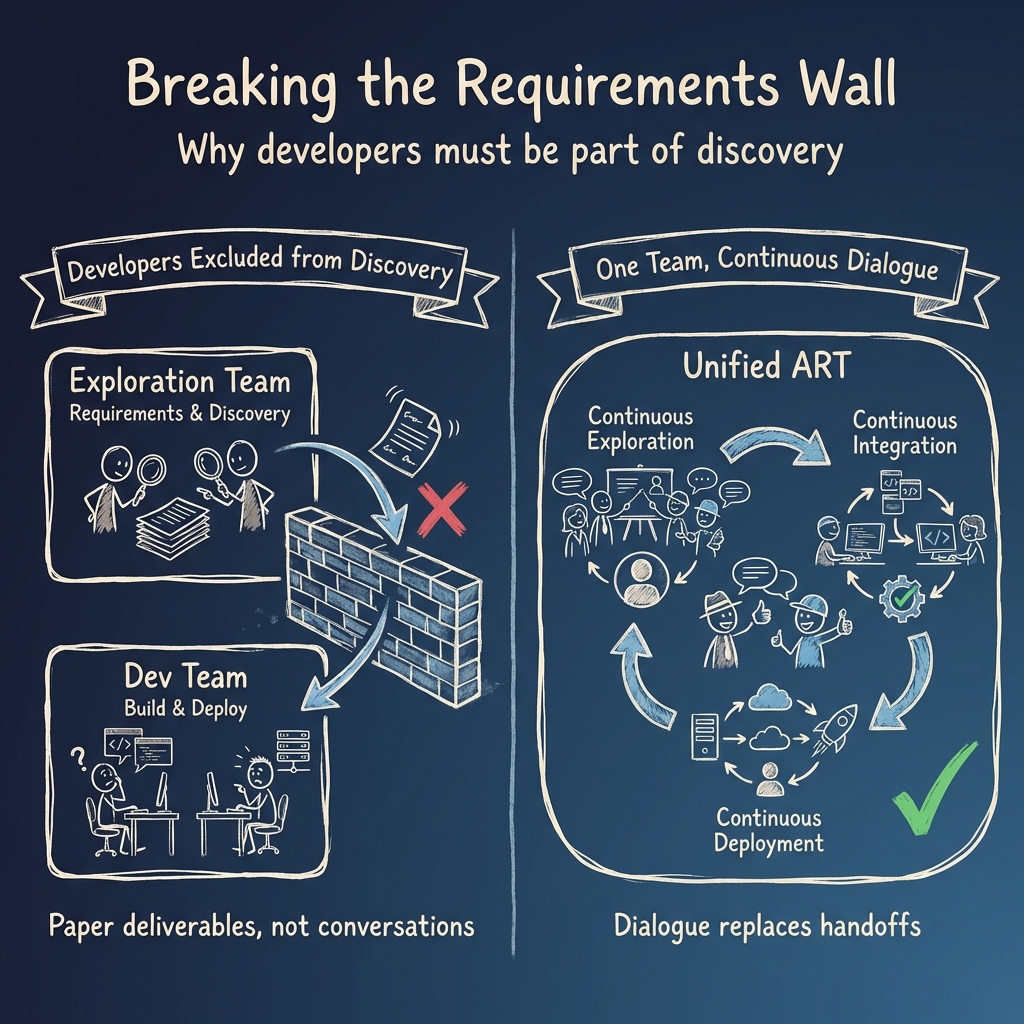

The Conway's Law Trap: ARTs Organized by Contract

Melvin Conway observed that "organizations designing systems are forced to create designs that mirror their own communication structures." This is just as true for the software delivery organization as it is for the system being built.

Here's the common mistake we see repeatedly: A program structures its ARTs to mirror its contracts. One contract handles "Requirements and Exploration." Another handles "Development and Integration."

The result: requirements become a paper deliverable rather than a conversation. The Exploration ART runs discovery and hands requirements to a Dev/Integration ART that had no part in the discussion. This isn't just inefficient; it violates a core principle of agile delivery.

All agile methods treat dialogue between the people who understand the mission and the people who will build the system as essential, not optional. In practice, this means both exploration staff and the system integrator need to be part of continous discovery. Without their voices, you get constant rework every PI: the System Integrator spends weeks figuring out what was meant, the government pays twice for discovery, and accountability dissolves across contract lines.

💡Separate Contracts Can Still Work

This doesn't mean we can't have separate contracts for exploration and development. It just means the contracts need to be set up to reward collaboration and shared accountability.

This isn't a people problem. It's Conway's Law in action. Split Continuous Exploration from Continuous Integration by ART, and you've created a built-in problem that needs careful planning to fix.

The Fix: Badgeless Teams

Every ART should own the entire Continuous Delivery Pipeline: Continuous Exploration, Continuous Integration, and Continuous Deployment. All three on the same train.

This absolutely CAN work in multi-vendor environments. We've seen it succeed and we've seen it struggle. The difference is careful planning: contract language that mandates collaboration, shared metrics that align incentives, and team structures that mix vendors and government staff.

The "badgeless" approach means engineers from Vendor A work alongside BAs from Vendor B and product owners from the agency. No one asks "which contract are you on?" during standups.

💡What is Continuous Exploration?

A repeatable loop of Discover, Test, and Decide embedded in the same train that builds and deploys software. It's not a separate "requirements phase." It's continuous validation of what to build next, running in parallel with delivery. Key roles include System Architects, Senior Developers, Business Analysts, and User Experience staff.

A Note on CO/COR Authority:

Badgeless doesn't mean contractors directing other contractors. That's a legitimate concern and a real compliance boundary. We address it through intentional training: every team member understands who can direct whom, what decisions require COR involvement, and how to escalate appropriately. Weekly cross-vendor syncs with the COR provide a structured forum to find problems early and resolve issues before they become compliance problems. The result: integrated work with clear authority lines.

The Myth: "We Need Separate Teams to Hold Vendors Accountable"

This is the objection we hear most often. Program offices believe that mixing vendors on the same teams will make it impossible to hold any single vendor accountable. If everyone's on the same team, who do you blame when it fails?

The logic sounds reasonable. It's also wrong.

Siloed contracts don't create accountability. They create finger-pointing. When Vendor A's requirements are "misinterpreted" by Vendor B's developers, each vendor blames the other. The government is left settling arguments instead of shipping software.

The Reality: Hold vendors accountable for shared metrics, not isolated deliverables.

Effective multi-vendor accountability looks like this:

| Siloed Accountability | Shared Accountability |

|---|

When all vendors on a train share responsibility for lead time, they have incentive to eliminate friction in handoffs. When they're rated on collaboration, they stop hoarding information. When turnover affects everyone's performance rating, they stop constantly replacing people.

What this looks like in practice: On one of the most successful agile implementations we've been part of, every team mixed people from three different vendors. They used a "best athlete" approach for all positions. No corporate divisions. People could point fingers, but only at individuals, not companies. We held people accountable through collaboration scores rated by peers from all vendors and the government. People who didn't perform were replaced, and vendors knew that replacement meant they could lose the position to another vendor. The result: vendors were heavily incentivized to provide high-quality people, and the finger-pointing stopped. For reasons beyond the scope of this article, this isn't the right approach for every program. It's a tool in the toolbox, not a one-size-fits-all solution.

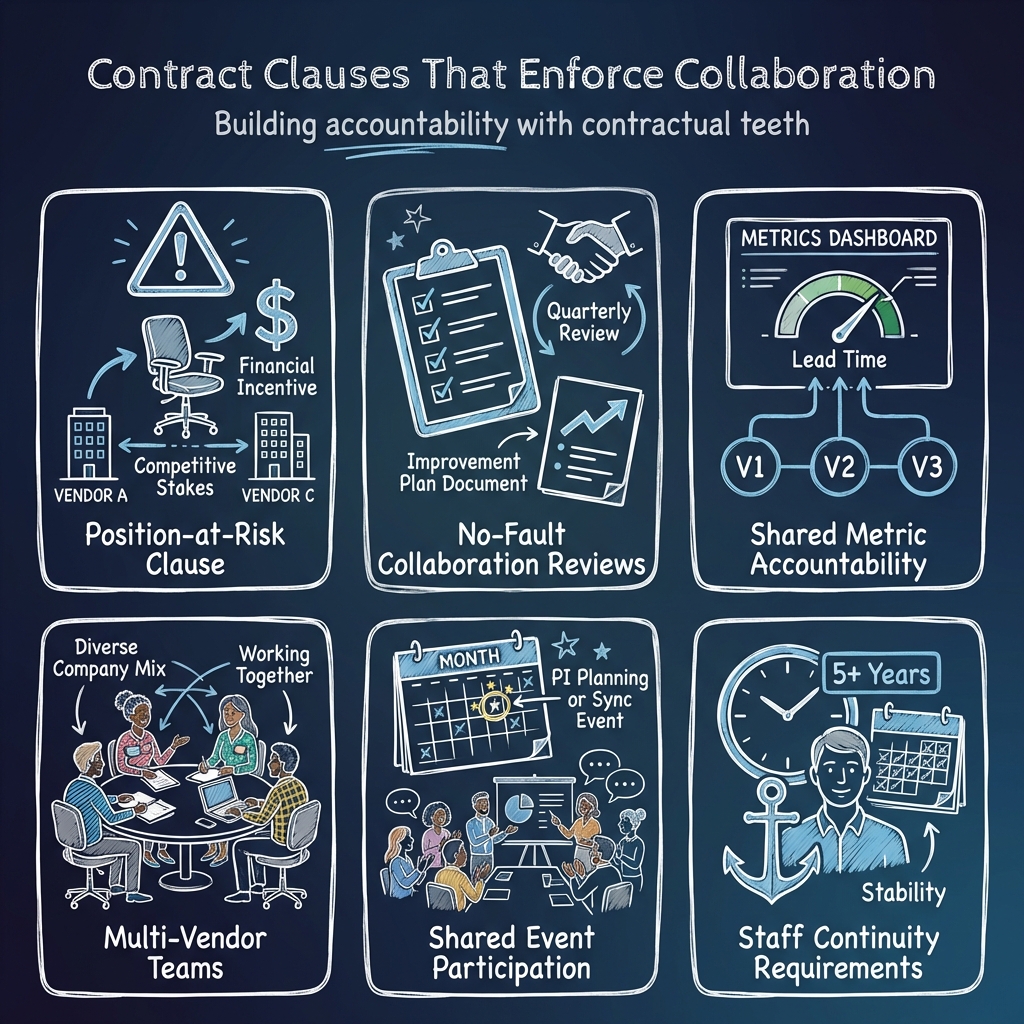

Contract Clauses That Enforce Collaboration

Accountability without enforcement power is wishful thinking. We support multi-vendor collaboration with contract language and incentives, not just goodwill.

What to require in contracts:

- Position-at-Risk for Poor Performance: If vendor staff are replaced due to poor collaboration or performance, the position can be restaffed by any qualified vendor on the contract. Vendors with repeated replacements or excessive turnover can lose the ability to staff new positions or be removed from the contract entirely. This creates a strong financial reason for vendors to provide A-level staff.

- No-Fault Collaboration Reviews: Quarterly assessments of cross-vendor collaboration, separate from individual vendor performance reviews, with documented improvement plans.

- Shared Metric Accountability: Contract incentives (award fee, CPAF criteria) tied to train-level metrics: lead time, release predictability, defect escape rate.

- Cross-Functional Team Composition: The government, with support from a completely independent agile coach, identifies team composition with input from all vendors.

- Shared Event Participation: All vendor staff from appropriate roles must attend and contribute to PI Planning, Inspect & Adapt, and cross-ART sync events. Failure to meet the spirit and letter of contribution requirements leads to corrective action.

- Staff Continuity Requirements: Minimum tenure requirements for key roles. Turnover above threshold triggers fee reduction.

These clauses aren't theoretical. They're deployed on programs that have successfully run multi-vendor SAFe implementations.

Ready to discuss multi-vendor contracts? Packaged Agile has developed specific contract clause templates and metric frameworks for multi-vendor collaboration in federal SAFe environments. If you're navigating a multi-vendor train (or about to stand one up), reach out for a 30-minute call to discuss what's worked—and we'll share a sample clause pack.

The Metrics That Actually Matter

If your executive dashboard shows velocity, burndown, and PI Planning attendance, you're measuring the theater, not the mission.

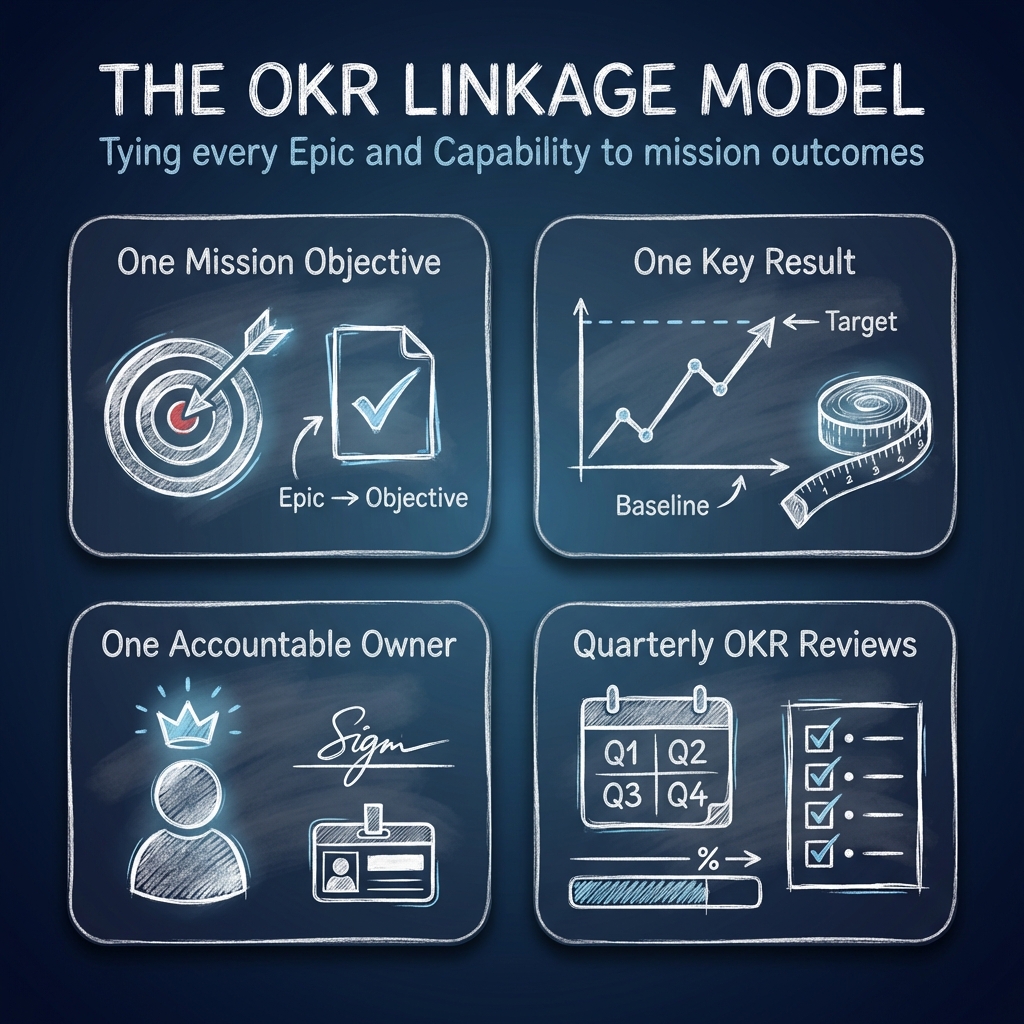

For better results, we want to replace compliance metrics with mission metrics.

| Compliance Metric | Mission Metric |

|---|

The 18th State of Agile Report (2025) backs this up: 76% of organizations report increased ROI scrutiny from leadership. But 52% struggle to track business impact, and 53% struggle to prioritize the right work.[] Leadership wants outcomes. Programs are delivering activity reports.

The solution isn't better reporting alone. It's linking every major work item (Epic and Capability) to one mission objective, one measurable key result, one accountable owner, and quarterly OKR reviews.

These OKRs are defined upfront. Executives know from day one that they will be measured on them. And here's the built-in accountability mechanism: if an Epic or Capability shows insufficient progress for two consecutive quarters, trigger a mandatory review. The options are clear: change the team, pause the work to replan, or stop it entirely.

Leaders hate stopping work or changing teams because it takes time. But that discomfort is the point. If you've spent three to six months with limited progress, you either have the wrong team or you haven't coordinated outside dependencies well enough to justify the spend. Either way, continuing without intervention isn't agile. It's wishful thinking with a burndown chart.

The 90-Day Mission-Results Protocol

So how do you actually implement all of this: the right metrics, OKR-linked work, forcing functions, and governance changes? We use what we call the Mission Results Protocol to turn a red program green. The protocol is a set of practices and tools that help teams deliver software to users, with empowered Product Owners, dynamic roadmaps, and metrics that measure lead time and mission outcomes. Here is the standard 90-day installation sequence (adjusted for your situation):

Phase 1 (Days 0-30): Diagnostic & Baseline

- Select Value Streams: Pick 1-2 value streams with high mission pain.

- Define OKRs: Define 3-5 Objectives and Key Results with baselines and name the accountable mission owner.

- Map Flow: Map end-to-end flow: quantify where work waits (decisions, environments, security compliance gates, interfaces).

- Start Readiness: Stand up the Partner Readiness Protocol for upcoming roadmap items (assessments 6-12 months ahead).

Phase 2 (Days 31-60): Delivery & Governance Operating Model Cutover

- Map Decisions: Implement decision-rights map with decision timelines (Service Level Agreements) including senior stakeholder escalation paths.

- Reform Planning: Restructure PI Planning so business owners get value (agenda built for their decisions, not engineer readouts).

- Commit Capacity: Formalize mission-side capacity commitments, or renegotiate scope if they can't staff it.

- Unify Vendors: For multi-vendor trains: publish a single integration plan, demo standard, and cross-vendor defect policy.

- Align Procurement: Align procurement and FAR timelines with delivery cadence where possible.

- Train Authority: For badgeless multi-vendor teams: implement CO/COR authority training and weekly cross-vendor syncs.

Phase 3 (Days 61-90): Value Realization

- Review Outcomes: Run monthly outcome reviews: show OKR movement or explain why not.

- Track Trends: Show lead time and reliability trendlines (not just status).

- Enforce Discipline: Kill or pause work that shows insufficient progress for two quarters, cannot link to an outcome, or lacks a committed decision-maker.

- Expand Cautiously: Expand to the next value stream only after meeting readiness and flow criteria.

Stop Funding Theater

The pattern is consistent across industry data and federal experience: SAFe events increase visibility and create the appearance of control. But without mission-side capacity, unified governance, dynamic roadmaps, and outcome-linked metrics, that visibility is an illusion.

According to the 18th State of Agile Report (2025), only 13% of organizations say agile is truly embedded across business and technology. Only 15% say business leaders actively shape agile practices.[] The other 85% are running process on top of bureaucracy, and wondering why reliability keeps declining.

SAFe isn't the problem. SAFe as box-checking is the problem.

The solution is straightforward, even if it's not easy: treat mission outcomes as the product. Define the staffing model required for mission participation, and enforce it. Fix slow decision-making with unified governance. Require partners to meet readiness requirements before starting. Structure contracts for collaboration, not finger-pointing. Measure what matters: lead time, reliability, outcomes.

Or keep perfecting your PI Planning events while the mission waits.

Frequently Asked Questions

References

[1] Digital.ai, "18th State of Agile Report," 2025.

For federal leaders navigating large-scale agile transformations, Packaged Agile deploys the Mission-Results Protocol to turn troubled programs around in 90 days. Contact us to discuss your situation.